Why is French Nuclear Failing So Miserably?

For years, nuclear advocates have pointed to France as a paragon of scalable and reliable decarbonization. But when it was most desperately needed, French nuclear collapsed. What gives?

For the last two weeks, armed police have been dismantling barricades and clearing climate activists from a vacant town in Germany due to be destroyed by the expansion of a coal mine. This represents a particularly uncomfortable situation for German policymakers, particularly the Greens.

Germany has long been lionized as a climate leader and a pioneer in the deployment of renewable energy. Germany will have invested over $500 billion euros through 2025 in its energy transition – the Energiewende – in pursuit of a renewable, nuclear-free economy.

However, German leaders can’t deny the absolute necessity of coal in facing its current energy crisis.

This year, Germany used more fossil fuels for its electricity than in any year since 2018, despite having built 45% more solar and 25% more offshore wind capacity since then. Hard coal consumption for electricity production increased by over 16% from 2021, driven by the government’s orders to turn retired coal plants back on and delay scheduled closures. The price tag is eye watering – nearly half a trillion euros set aside to secure oil, natural gas, and coal (some of which would normally be bound for energy-starved countries.)

Many have been sounding the alarm on the foolishness of Germany's energy strategy for years. After all, one simply has to look to its western neighbor, France, to find a working example of a low-carbon, low-cost, secure electricity system.

In response to the oil shocks of the 1970s, France famously built a massive amount of nuclear power to reduce its dependence on imported fossil fuels. Between 2010 and 2020, France generated more than 70% of its electricity from nuclear, making it the largest share of nuclear power worldwide. As a result, French electricity has been roughly ten times cleaner than Germany’s at nearly half the cost.

But France has found itself in a crisis of its own. Nuclear production last year hit a 30-year low. On some days, day-ahead power prices were higher in France than anywhere else in the EU. Heading into the winter, half of the nuclear fleet was offline due to corrosion issues and delayed maintenance outages. Rather than exporting carbon-free electricity to Germany, France increased imports of coal-fired power from Germany.

Some are pointing to France’s energy woes as the danger in heavily relying on nuclear power.

“Nuclear reactor problems in France show need for diversified mix of renewables,” writes Frank Bass of the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “France may have to roll out organized blackouts too...the nuclear fleet is very old and cracking up,” commented Dr. Paul Dorfman, an associate fellow at the University of Sussex and an anti-nuclear campaigner.

Yet this abysmal performance hasn’t been seen in the US, which has a fleet larger and older than France’s. American nuclear plants operate at an average capacity factor of about 93%, meaning the fleet produces 93% of its maximum possible output. Meanwhile, the French fleet was just above 50% this year. The U.S. nuclear fleet has reliably and resiliently provided power through historic cold snaps, heat waves, and hurricanes.

So what’s happening in France? The truth is that France has worked very hard to achieve this collapse in nuclear production.

Commitment to “Competition”

The issues began with the creation of the continental European electricity market in the late 1990s. Prior to this, countries had their own systems for generating, transmitting, and distributing electricity. The EU decided to follow the growing trend of creating markets to foster competition and, theoretically, bring down prices.

Électricité de France (EDF), the country’s majority-state-owned utility, was against the market. EDF owns and operates the French nuclear fleet, with the majority of the plants paid off decades ago. The utility enjoyed high levels of public support due to its ability to provide cheap and reliable power. There was scarce competition within French borders.

However, Europe had around 40 gigawatts of extra power capacity, mostly from coal plants. At the time, coal was cheap. When the market opened, it was completely agnostic to dirty versus clean electricity – so no advantage for EDF’s carbon-free power. EDF knew its customers would demand wholesale prices aligned with a market flooded with cheap coal.

Unable to get the French government to push back on the European Commission’s measures, EDF management decided they would need to manipulate the market instead. If the nuclear fleet produced less electricity, scarcity would drive higher prices and thus profits.

EDF began taking steps to reduce its nuclear output while maintaining plausible deniability. Maintenance outages became longer and less-efficient so the plants could be offline longer. Investments focused on upgrading plants to meet the regulator’s new safety standards, but ignored uprates that would allow the plants to generate 10 to 25% more power. EDF began planning to decommission plants when they reached 40 years of operation, despite reactors of similar design and vintage around the world having had their lives extended to 80 years and perhaps beyond. The name of the game was to produce, but not too much.

By 2005, industrial customers in France were starting to complain. Rather than petition the government to tackle the problem of poor nuclear output, they advocated for special electricity price plans for themselves. In 2007, they got their wish. But some people asked, “why should only big industry get sweetheart energy deals?” In 2011, the more “democratic” ARENH (Accès Réglementé à l'Électricité Nucléaire Historique) was enacted. The law forced EDF to offer 100 TWH, or about 25% of its expected annual production then, to its competitors at a fixed price.

This system ended up being easy for competitors and traders to game in their favor because of the built-in optionality. Competitors could choose to buy this power – or not. This enabled electricity traders to buy low and sell high without having to take on the downside risk of buying when prices in the market fell below that fixed price.

This optionality created the possibility for arbitrage. For example, EDF competitors and energy traders can make contracts to sell electricity directly to customers who have high demand in the summer. That way, they know they would have customers when demand, and thus prices, are typically lower. They may even incur small losses on these contracts over the summer. However, when the winter comes and these competitors or traders have fewer contractual obligations, they can sell the cheap ARENH power into the market to get the much higher prices of winter.

Traders can take EDF’s power and make a profit without having to build or operate power plants at all. In attempting to make a tool to protect customers and disincentivize EDF’s bad behavior, the government ended up creating a system prone to arbitrage and cheating. This made it harder for EDF to profitably produce nuclear and reinforced the bad behavior.

Commitment to Alternatives

The trouble for French nuclear worsened when the European Commission set binding targets for increasing renewable energy in 2009. France had almost completely decarbonized its electricity already with nuclear. But the Commission didn’t count nuclear, despite it being carbon-free.

French policymakers viewed this not as an obstacle, but an opportunity. Fully aware of the manipulation happening in EDF, the government could erode the utility’s dominance in their electricity system by incentivizing other market participants to build wind and solar. Plus, solar and wind were popular with the public: win-win.

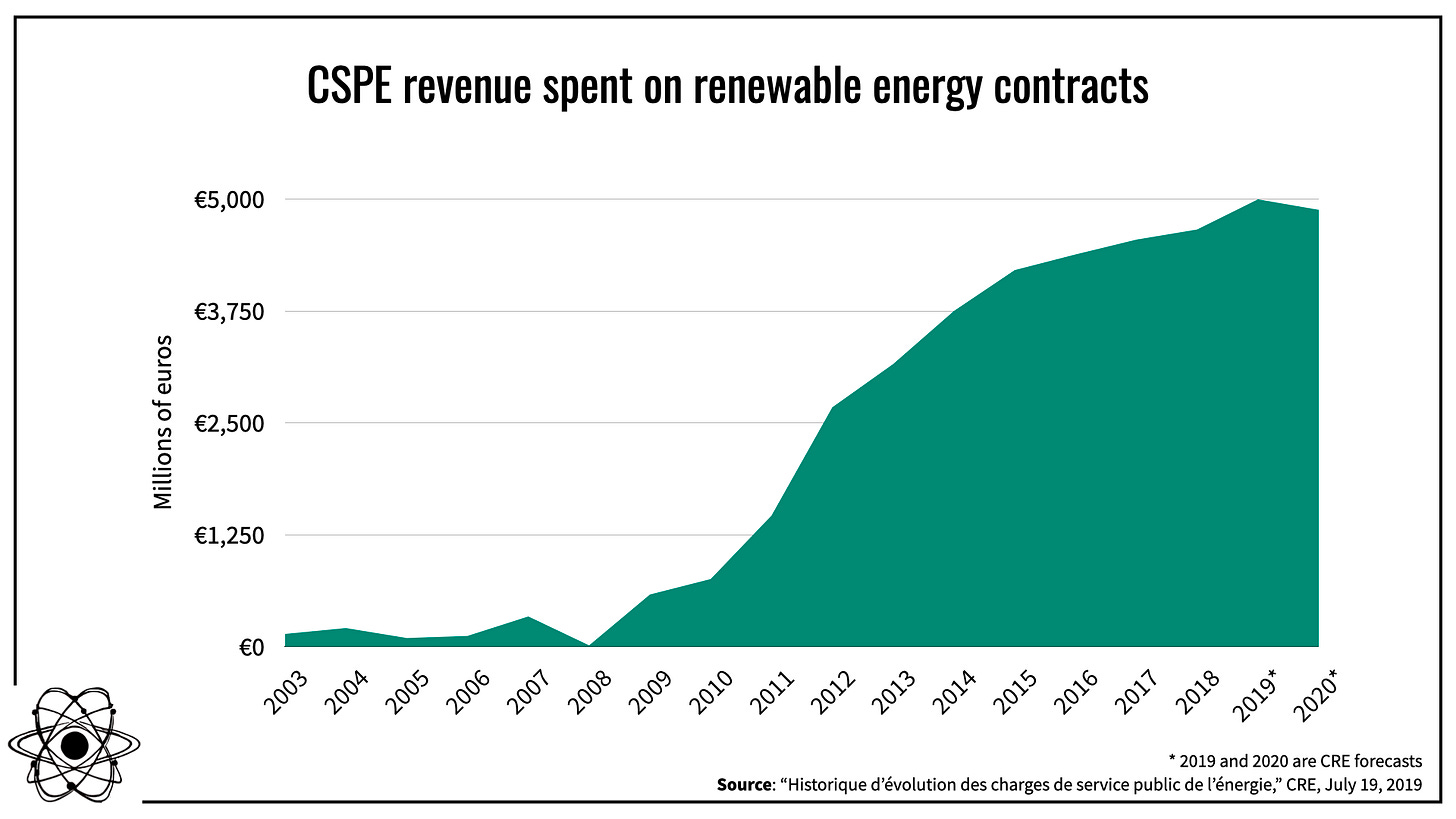

Thus in 2010, France introduced the Contribution au Service Public de l'Electricité (CSPE). CSPE is a tax on all electricity, passed on to consumers through their electricity bills. This tax is largely used to fund subsidies for wind and solar projects built primarily by private developers.

Renewables were also given priority on the French grid. EDF is responsible for paying large subsidies to solar and wind while waiting to collect enough revenue from their customers to cover them. When EDF has to turn down its nuclear to accommodate wind and solar (for no carbon benefit), the renewables debt on its books grows even bigger.

The result was a tax on the cleanest energy in France that made it even less competitive with dirty electricity from other countries.

Why invest in upgrades and efficient maintenance for a fleet that would need to be operated less and less, making it more and more unprofitable? Keeping marginal fossil fuels on the grid to drive up prices became more necessary for EDF to make money.

Commitment to Closing Nuclear

The most direct attack on nuclear in France came in 2014, when the National Assembly passed its “Energy Transition for Green Growth” into law. The policy mandates a reduction in nuclear from 75% of the electricity mix to 50% by 2025, while increasing its share of renewables to 32% by 2030. It also set a target for cutting France’s energy demand in half by 2050.

Nuclear legally had to make up a smaller share of a significantly smaller pie. The only option would be to double down on the existing strategy: plan nuclear closures, operate for fewer hours, and increase non-nuclear generation. And sure enough, that’s what happened.

EDF extended outages to keep plants offline longer. The government agreed to pay EDF 400 million euros to close a plant of exemplary performance that had recently been upgraded. When I traveled to France in 2017, engineers within EDF told our team that internal promotion was about rejecting a nuclear future in France and asking to work on renewables. Staffing culture within the nuclear division was neglected and talented young French people went elsewhere.

For the past two decades, France’s problem with nuclear power wasn't that it wasn’t good enough; it was that the government, operating utility, and technocrats in Brussels thought there was too much of it.

The fleet has been vandalized to the point of severe damage and it is underperforming as a result.

Nuclear’s Future in France

Fortunately for France, nuclear power is incredibly resilient. It took more than 20 years of purposeful destruction, embezzlement, and neglect to show serious signs of deterioration. While the current outages will be painful, the plants will recover. If they choose, the French could have a world-class, fully-upgraded fleet of carbon-free power plants at the end of this crisis.

That certainly appears to be what France wants. Less than two years after overseeing the closure of Fessenheim, Macron committed to extending the lives of all existing French nuclear plants. “What our country needs ... is the rebirth of France’s nuclear industry,” the President said last February. He announced plans to build six new reactors, with the possibility of eight more, to further reduce the country’s reliance on oil and gas.

But it’s unclear if France will right the ship. EDF’s debt is massive. The company’s flagship nuclear projects are massively over-budget and behind-schedule (ironically, the oldest plants like Fessenheim don’t have the flaws that are now shutting down newer plants as they await technical fixes.) Much of the new management at EDF doesn't have any experience in nuclear, having come up in a culture that prioritized renewables and ignored poor nuclear performance.

France already had a secure, low-cost, and low-carbon grid. But it was achieved decades before decarbonization was even a goal by a state-directed rollout of publicly-owned nuclear plants, not the subsidization of private renewables. Rather than offering itself as an alternative to Germany, France decided to follow their lead. Now, the French grid is less secure and more expensive for no carbon benefit.

France should serve as a cautionary tale for the rest of the world: if leaders and the public are allowed to forget why nuclear was built, that country may find itself back in the position that made nuclear necessary in the first place.

A remarkably thoughtful and well-informed article about French nuclear status!